Notes on Teaching Transformers Arithmetic

I’ve been wanting to learn more about LLMs and transformers, so I tried reproducing the results from Transformers Can Do Arithmetic with the Right Embeddings, an interesting paper on altering LLM architecture to allow more easily learning basic arithmetic.

This post contains an implementation of the core ideas of the paper, and my notes on both that implementation and core concepts of the paper. The goal is something like”the post to get a past version of myself with exactly the holes in my knowledge up to speed on the things I learned.” Your mileage will probably vary.

Anyway, the idea in the paper is to train a transformer on formulaic prompts like “27+34=61”, with the goal of being able to generalize to Out Of Distribution (OOD) numbers. To achieve this, the authors use an approach which they call “abacus encoding”:

- Numbers are written with the least significant digit first rather than last (i.e. “one hundred and twenty-three plus four hundred and fifty-six” is written 321+654).

- Digits are always tokenized as separate tokens. This is definitely not the case with models like OpenAI’s GPT series, with a substantial number of tokens in the language consisting of 2-digit or 3-digit numbers. This is presumably one reason otherwise quite intelligent LLMs are fairly bad at arithmetic: imagine having to learn from context that

765consists of the sequence of digits 7 6 5, or more famously that11consists of 1 1. It’s remarkable they can do any kind of reasoning about numbers at all. - There is a special positional encoding for numbers, a collection of 100 learned weight vectors recording the position of the ith digit in a number. E.g. our 321+654 example would get encode as the sequence:

- (Learned embedding of token “3”) + (Learned abacus encoding vector at position 1)

- (embedding of “2”) + (abacus encoding at position 2)

- (embedding of “1”) + (abacus@3)

- (embedding of “+”) + (abacus@0)

- (embedding of “6”) + (abacus@1)

- (embedding of “5”) + (abacus@2)

- (embedding of “4”) + (abacus@3)

- OK actually (3) won’t allow generalization because if we only train on 20-digit numbers, the abacus encoding at position 21 would never get any gradient updates and would just be random noise. To get around that, abacus encoding actually picks a random offset value and uses that as the “start” of all numbers. E.g. in our

312+654example, 3 and 6 might get the 39th abacus vector, 2 and 5 the 40th, etc.

They also use a “looped transformer” architecture, where a sequence of K transformer layers is “repeated” or “looped” N times, with the output of the last layer feeding back into the first layer. The idea is that this should eventually converge to a “fixed point” (i.e. looping more times yields the same output tensor. This allows economizing on the number of parameters in the model, while still allowing the network to be deep enough to show nontrivial behavior. There is some theoretical and empirical reasons this may be useful; they cite a few interesting papers:

- Looped Transformers as Programmable Computers, which gives a mechanism for building arbitrary circuits in a transformer. A fairly neat construction, though I haven’t dived into this one.

- Looped Transformers are Better at Learning Learning Algorithms, which shows that looping a transformer can improve performance on a linear regression task. Not useful by itself since linear regression is solved by much faster algorithms, but as with this paper, it’s suggestive that looped transformers may be useful for other kinds of reasoning.

They needed two tricks to make looping work:

- Add the original input to the output at each loop. This presumably prevents the outputs decaying or blowing up to infinity, though then they needed to not do that for multiplication.

- When computing loss, run the input on a fixed number of loops and make a “convex combination” of that (cross-entropy) loss with the loss from a smaller random number of loops.

Then they train the network on a bunch of problem instances like 1+1=2 or 12+13=25, up to 20 digits, with the number of digits being chosen at random, then the numbers being chosen at random to match that number of digits (i.e. each combination of digits is equally likely in the training data, rather than 81% of them consisting of twenty digit numbers).

Since the problem instances are themselves random (i.e. cannot be predicted), they “mask” the tokens up to the equals sign, so they don’t add a bunch of noise with high loss values from failing to predict random input. In other words, they only train on next-token prediction after the equals size.

Results

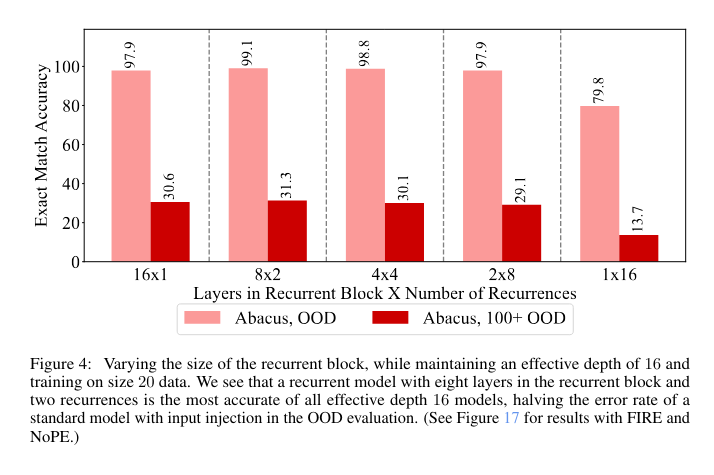

They found that the models using abacus encoding were able to generalize to out-of-distribution numbers with high 90’s accuracy. Most interestingly, they found that despite having a smaller number of parameters, the looped transformers performed somewhat better than one deep transformer, with two loops of eigth layers being the most performant among “effective depth 16” transformers. They were able to extend these results to some other operations, suggesting that abacus encoding may be helpful for some kinds of general algorithmic tasks.

Reproducing the results

One cool thing about this paper is that it’s fairly modest in terms of GPU hardware required, and could probably even train on a CPU. The models are mostly quite small, and I was able to (partly) reproduce the addition results on my 8GB Nvidia 4060 GPU.

First, let’s define the tokenizer:

class SimpleTokenizer:

def __init__(self):

self.alphabet = "0123456789-+*=$" # $ is EOS token

self.token_to_idx = {char: idx for idx, char in enumerate(self.alphabet)}

self.idx_to_token = {idx: char for char, idx in self.token_to_idx.items()}

self.vocab_size = len(self.alphabet)

self.eos_token = "$"

self.eos_id = self.token_to_idx["$"]

self.digit_tokens = set("0123456789")

self.digit_token_ids = set(

self.token_to_idx[digit] for digit in self.digit_tokens

)

def encode(self, text, add_eos=True):

"""Convert string to list of token indices"""

tokens = [self.token_to_idx[char] for char in text]

if add_eos:

tokens.append(self.eos_id)

return tokens

def decode(self, indices, remove_eos=True):

"""Convert list of token indices back to string"""

if remove_eos and indices[-1] == self.eos_id:

indices = indices[:-1]

return "".join(self.idx_to_token[idx] for idx in indices)

def is_digit(self, token_id):

return token_id in self.digit_token_ids

assert SimpleTokenizer().encode('1234') == [1, 2, 3, 4, 14]

SimpleTokenizer().encode('1234$')

[1, 2, 3, 4, 14, 14]

import torch

import random

from torch import nn

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

import torch.nn.functional as F

import json

import subprocess

from tqdm import tqdm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

class AbacusPositionalEncoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, d_model, max_seq_len=512, k=100):

super().__init__()

self.d_model = d_model

self.max_seq_len = max_seq_len

self.k = k

self.positional_embeddings = nn.Embedding(max_seq_len, d_model)

def find_numbers(self, tokens, tokenizer) -> list[list[int]]:

"""

Returns a list of lists of indices of digits in each number.

e.g. the tokens for `+12=34` would return [[1, 2], [4, 5]]

"""

cur_span = []

spans = []

for i, token in enumerate(tokens):

if tokenizer.is_digit(token):

cur_span.append(i)

else:

if cur_span:

spans.append(cur_span)

cur_span = []

if cur_span:

spans.append(cur_span)

return spans

def forward(self, x, tokenizer, training=True):

# Here we're given a "batch" of substrings of problem instances that will run

# on the GPU in one go.

batch_size, seq_len = x.shape

device = x.device

positions = torch.zeros(batch_size, seq_len, dtype=torch.long, device=device)

for i in range(batch_size):

spans = self.find_numbers(x[i].tolist(), tokenizer)

longest_number = max(len(span) for span in spans)

if training:

# Choose a random offset to allow for generalization. Note that since

# I created an embedding value for the entire context length, this can

# in principle generalize more than in the paper. Bug? Feature?

offset = random.randint(

0,

min(self.max_seq_len - longest_number, self.k - 1),

)

else:

offset = 0

for span in spans:

for j, pos in enumerate(span, 1):

positions[i, pos] = offset + j

embeddings = self.positional_embeddings(positions)

return embeddings

Here we define an nn.module object, which is basically a tensor (multidimensional array) of weights with an activation function defined in forward. When a tensor is run through a forward pass in training mode, pytorch keeps track of of how it was computed, so that gradients can be computed relative to those weights. Then on the backward pass, torch is able to compute a gradient from a function that was implicitly implemented in python code (in this case computing an index for the embedding). If you were to write out the entire neural net for one training instance as a big algebraic expression these weights would be like free variables, so part of the dimension of the gradient. If you move a model to a “device” like “cuda” (Nvidia) or “mps” (MacOS), it will automatically use efficient drivers to compute the forward pass or gradient in parallel. Pretty cool!

For example:

import math

x = torch.tensor([2.0], requires_grad=True)

y = torch.tensor([3.0], requires_grad=True)

def f(x, y):

return x ** 2 + torch.sin(y)

z = f(x, y)

z.backward()

print(f"Torch: {z.item()=} ; {x.grad.item()=} ; {y.grad.item()=}")

# Computing gradients by hand:

dz_dx, dz_dy = 2 * 2.0, math.cos(3.0)

print(f"Calc III: ∂z/∂x = {dz_dx} ; ∂z/∂y = {dz_dy}")

Torch: z.item()=4.141119956970215 ; x.grad.item()=4.0 ; y.grad.item()=-0.9899924993515015

Calc III: ∂z/∂x = 4.0 ; ∂z/∂y = -0.9899924966004454

Now let’s define a transformer layer using the extremely cool but poorly packaged flash-attn module. I had almost no luck getting it to compile from source, and they didn’t push wheels to pypi (presumably because different wheels are required for different versions of torch). I found it easiest to install by specifying a particular wheel to download, but ymmv:

flash-attn @ https://github.com/Dao-AILab/flash-attention/releases/download/v2.7.2.post1/flash_attn-2.7.2.post1+cu12torch2.5cxx11abiFALSE-cp312-cp312-linux_x86_64.whl

Use of flash attention differs from the paper, but should be faster and more memory efficient during training.

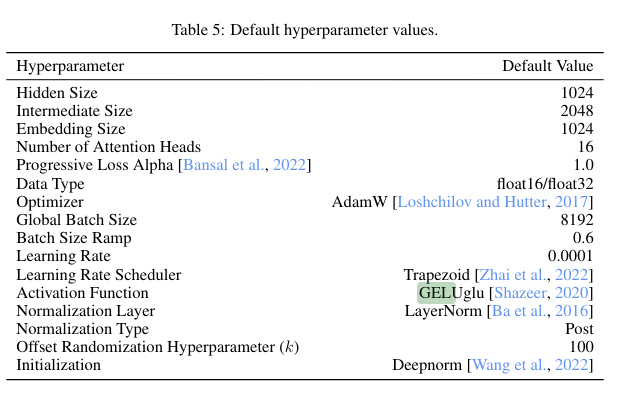

Note that this library requires 16-bit floats and cuda. The use of 16 bit floats in ML somehow feels extremely retro to me: more something you’d expect from a Sega Dreamcast than extremely advanced machine learning like modern LLMs. But you can’t argue with results!

# Note: this class was like 95% written by Claude Sonnet 3.5.

from flash_attn import flash_attn_func

class FlashDecoderLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

d_model=1024, # Model dimension from paper

nhead=16, # Number of attention heads from paper

d_ff=2048, # FFN intermediate dimension from paper

dropout=0.0, # They use no dropout during inference

activation="gelu",

layer_norm_eps=1e-12,

use_input_injection=True, # Add input to each layer as in paper

):

super().__init__()

assert d_model % nhead == 0, "d_model must be divisible by nhead"

self.d_model = d_model

self.nhead = nhead

self.head_dim = d_model // nhead

self.use_input_injection = use_input_injection

# Self-attention

self.qkv_proj = nn.Linear(d_model, 3 * d_model, bias=True)

self.out_proj = nn.Linear(d_model, d_model, bias=True)

# Normalization layers

self.norm1 = nn.LayerNorm(d_model, eps=layer_norm_eps)

self.norm2 = nn.LayerNorm(d_model, eps=layer_norm_eps)

# Feed-forward network

self.ff = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(d_model, d_ff),

nn.GELU() if activation == "gelu" else nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(d_ff, d_model),

)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

self.scaling = float(self.head_dim) ** -0.5

def forward(

self,

x: torch.Tensor,

positions: torch.Tensor,

input_injection: torch.Tensor = None,

key_padding_mask=None,

need_weights=False,

causal=True,

):

"""

Args:

x: Input tensor of shape (batch_size, seq_len, d_model)

positions: Position encodings from AbacusPositionalEncoder

input_injection: Original input for skip connections

key_padding_mask: Mask for padded tokens

need_weights: Whether to return attention weights

causal: Whether to apply causal masking

"""

shortcut = x

x = self.norm1(x)

# Add input injection if enabled

if self.use_input_injection and input_injection is not None:

x = x + input_injection

# Project to q, k, v

batch_size, seq_len = x.shape[:2]

qkv = self.qkv_proj(x)

qkv = qkv.reshape(batch_size, seq_len, 3, self.nhead, self.head_dim)

# Reshape positions to match head dimensions

positions = positions.view(batch_size, seq_len, 1, self.nhead, self.head_dim)

# Add positional embeddings to q, k only

qkv[:, :, :2] = qkv[:, :, :2] + positions

# Split into q, k, v

q, k, v = qkv.unbind(dim=2)

# Cast to fp16 for flash attention

q = q.to(torch.float16)

k = k.to(torch.float16)

v = v.to(torch.float16)

# Run flash attention

attn_output = flash_attn_func(

q,

k,

v,

dropout_p=self.dropout.p if self.training else 0.0,

softmax_scale=self.scaling,

causal=causal,

)

# Cast back to original dtype

attn_output = attn_output.to(x.dtype)

# Project output

attn_output = attn_output.reshape(batch_size, seq_len, self.d_model)

output = self.out_proj(attn_output)

# First residual connection

x = shortcut + self.dropout(output)

# FFN

shortcut = x

x = self.norm2(x)

if self.use_input_injection and input_injection is not None:

x = x + input_injection

x = shortcut + self.dropout(self.ff(x))

return x

Some notes on terminology for LLM n00bs like myself

“Attention Heads”

These are the fundamental insight of transformer architecture, consisting of three linear transformations (which seem to be called “projections” in ML literature whether or not they are “projections” in the mathematical sense): “queries”, “keys” and “values”.

Here qkv_proj is three square matrices “on top of each other”, which take in d_model=1024 vectors and output three concatenated vectors (query, key and value). When we “project” qkv = self.qkv_proj(x), we end up with something that has one 3*d_model vector for each (batch, sequence_position) pair, which gets reshaped and “unbound” into (Q,K,V) tensors. For a given batch and head index, that’s three matrices of dimension (seq_len, head_dim), and the flash attention does the following:

- Compute

Q@K^Tto get a matrix of shape(seq_len, seq_len). - Transform it with scaling and “softmax” (see below) to get attention weights. You can think of these as how much each token should attend to every other in the

d_head=64dimensional subspace of the “values” space for that layer. - Multiply that weights matrix by the “values” projection of that 64-d subspace to get a

head_dimvector for each head. - Apply “dropout” and “causal masking”:

- Dropout is a way to randomly exclude a subset (e.g. 20%) of weights from the gradient on each update to prevent overfitting the data and undergeneralizing. The NN needs to represent the same data in multiple compressed ways to survive dropout.

- Causal masking forces attention weights to be zero for all “future” tokens further in the sequence, roughly reflecting the intuition that the model is reading the data in order.

- Concatenate the data for each head together to get a d_model vector.

Note: the “flash” part just means that computation is split up to do it in a more cache- and memory-efficient way for modern GPUs.

At a mathematical level, the Query-Key part for each head is equivalent to a single linear map, since this is an “auto-regressive” model with “self-attention” (i.e. it’s working on the same space as input and output). The names seem to come from “encoder-decoder” transformer archectures used for translation, where in the decoder, the key domain and query domain were different (e.g. corresponding to embeddings of English and French). See this SO thread. For autoregressive models like GPT, I presume separating them into two kinds of matrices has some advantage, e.g. better compatibility with hardware or empirically works better with gradient descent.

After that, we do the “feed forward” part, which:

- Does a linear map (“projects”) into a higher dimensional (2048-dimensional) space

- Applies a nonlinear transform on the data (RELU/GELU, see below).

- Another linear map back into

d_modelspace, and on to the next layer.

“softmax”

A function which turns any list of numbers into a probability distribution, defined by:

\[\left(x_0, x_1, \ldots x_k\right) \mapsto \frac{1}{\sum_{i=0}^k \exp(x_i)}\cdot \left(\exp(x_0), \exp(x_1), ... \exp(x_k)\right)\]The name seems to come from the fact that if one of the arguments is significantly larger than the others, its softmax value will be near 1 and other values will be near 0. This is a smooth approximation of the function that maps a vector to one that is zero everywhere except at the largest index where it is 1 (sometimes called “argmax” or a “1-hot encoding” of the maximum index).

Aside 1: this has the nice property that it maps -inf values to 0.

Aside 2: Softmax has an absolutely fundamental property when used with categorical outputs that generalizes logistic regression. When the final layer has a softmax and the model is trained with cross-entropy loss, then the earlier layer will learn to produce “logits” (outputs of a layer in a NN) which when passed to softmax approximate a probability distribution on the conditional probabilities of the target distribution. This can be interpreted as “confidence” in many domains. This will be useful when we get to “perplexity” below.

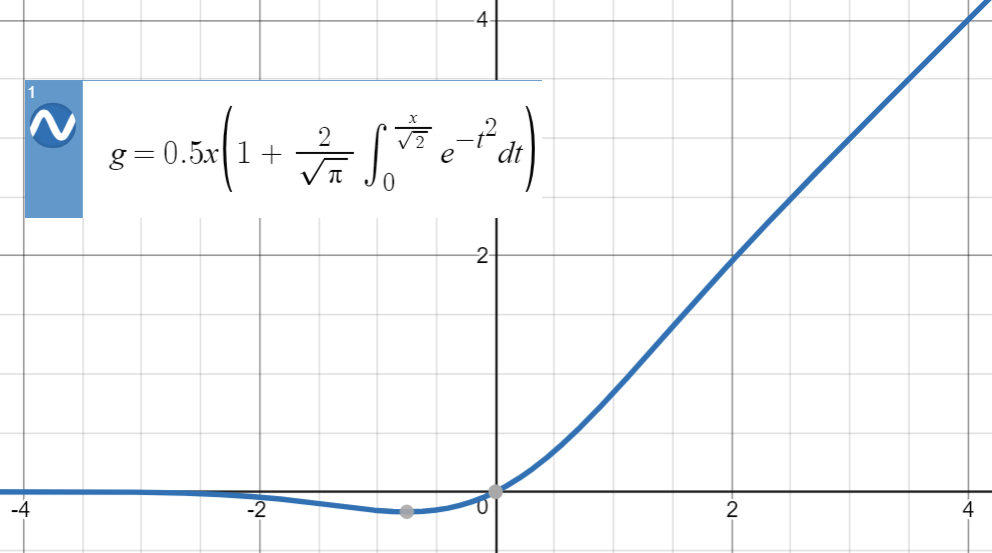

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) & GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit)

ReLU is a non-smooth, piecewise linear function defined by:

\[x \mapsto \max(x, 0)\]GELU is a function with a very similar-looking graph, but has some nonzero gradient below 0. It’s defined as $x\mapsto x\cdot \phi(x)$, where $\phi$ is the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution. See this Stackexchange answer where the graph below is from.

Both functions give some threshold “nonlinearity”, and a gradient that allows “muting” some nodes in the network. ReLU is like a hard switch where once it gets to 0. No gradients “from below” will have an effect on a zeroed out ReLU activation, while GELU provides a way of turning nodes “back on” since it has nonzero gradients below 0. In pytorch, neither function has any learnable parameters.

Graph of GELU:

Loop It!

This is somewhat more straightforward. We define a stack of layers with a given size and a max number of loops. We’ll choose 1 layer deep and 16 loops, which the paper found worked OK and is faster than the $8\times 2$ architecture they found works best. Then in forward, we loop that number of times, or some smaller number of times for the “random loop” part.

class FlashDecoderStack(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

recurrent_block_size=1, # Number of unique layers

num_recurrences=16, # Number of times to reuse layers

**layer_kwargs,

):

super().__init__()

self.recurrent_block_size = recurrent_block_size

self.num_recurrences = num_recurrences

# Create the recurrent block of layers

self.layers = nn.ModuleList(

[FlashDecoderLayer(**layer_kwargs) for _ in range(recurrent_block_size)]

)

def forward(self, x, positions, num_recurrences=None, **kwargs):

# Store original input for input injection

input_injection = x if self.layers[0].use_input_injection else None

if num_recurrences is None:

num_recurrences = self.num_recurrences

# Apply layers with recurrence

for _ in range(num_recurrences):

for layer in self.layers:

x = layer(x, positions, input_injection=input_injection, **kwargs)

return x

And finally, we define the full transformer module. Note that in the loss computation, we don’t need to apply softmax first, since torch’s CrossEntropyLoss accepts either a probability distribution or a list of target class IDs (in which case it does the equivalent of log softmax to compute the loss).

class ArithmeticTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

d_model=1024,

nhead=16,

recurrent_block_size=16,

num_recurrences=1,

d_ff=2048,

dropout=0.0,

max_seq_len=512,

):

super().__init__()

self.tokenizer = SimpleTokenizer()

vocab_size = self.tokenizer.vocab_size

self.token_embeddings = nn.Embedding(vocab_size, d_model)

self.pos_encoder = AbacusPositionalEncoder(d_model, max_seq_len)

self.decoder_stack = FlashDecoderStack(

recurrent_block_size=recurrent_block_size,

num_recurrences=num_recurrences,

d_model=d_model,

nhead=nhead,

d_ff=d_ff,

dropout=dropout,

)

self.output_projection = nn.Linear(d_model, vocab_size)

self.max_seq_len = max_seq_len

def forward(self, input_ids, labels=None, num_recurrences=None):

x = self.token_embeddings(input_ids)

pos = self.pos_encoder(input_ids, self.tokenizer)

x = self.decoder_stack(

x,

positions=pos,

key_padding_mask=None,

causal=True,

num_recurrences=num_recurrences,

)

logits = self.output_projection(x)

if labels is not None:

# Shift labels and logits

shift_logits = logits[..., :-1, :].contiguous()

shift_labels = labels[..., 1:].contiguous()

# Calculate loss only on answer tokens

loss = F.cross_entropy(

shift_logits.view(-1, shift_logits.size(-1)),

shift_labels.view(-1),

ignore_index=-100, # Ignore padded tokens

)

return {"loss": loss, "logits": logits}

return {"logits": logits}

Generate and encode data:

This is a small hack around the torch Dataset class, overridding __getitem__ to return a tokenized problem instance with a random number of digits between 1 and 20. Note that we use -100 for tokens we want to mask (up to the = and after the $), as defined in the ignore_index parameter above.

class ArithmeticDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, max_digits=20, num_samples=20000000):

self.tokenizer = SimpleTokenizer()

self.max_digits = max_digits

self.num_samples = num_samples

def __len__(self):

return self.num_samples

def generate_number(self, num_digits):

"""Generate a number with exactly num_digits digits"""

if num_digits == 1:

return random.randint(0, 9)

return random.randint(

0 if num_digits == 1 else 10 ** (num_digits - 1),

(10**num_digits) - 1,

)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

# Sample lengths uniformly

len1 = random.randint(1, self.max_digits)

len2 = random.randint(1, self.max_digits)

# Generate numbers with exact lengths

num1 = self.generate_number(len1)

num2 = self.generate_number(len2)

# Create the problem string (reversed order as per paper)

problem = str(num1)[::-1] + "+" + str(num2)[::-1] + "="

answer = str(num1 + num2)[::-1]

# Convert to tokens

input_tokens = self.tokenizer.encode(problem, add_eos=False)

assert (

input_tokens[-1] == self.tokenizer.token_to_idx["="]

), "Problem must end with ="

# Create mask labels with -100 for all positions up to and including =

labels = [-100] * len(input_tokens)

target_tokens = self.tokenizer.encode(answer)

assert target_tokens[-1] == self.tokenizer.eos_id, "Answer must end with EOS"

input_tokens.extend(target_tokens)

labels.extend(target_tokens)

# Calculate maximum possible sequence length

max_seq_len = (self.max_digits * 2) + 2 # Two numbers + '+' and '=' signs

max_answer_len = (

self.max_digits + 1 + 1

) # Max answer length (1 digit more than max digits) + EOS

total_seq_len = max_seq_len + max_answer_len

# Pad input_tokens to max_seq_len

input_tokens = input_tokens + [self.tokenizer.eos_id] * (

total_seq_len - len(input_tokens)

)

# Pad labels to total_seq_len

labels.extend([-100] * (total_seq_len - len(labels)))

return {

"input_ids": torch.tensor(input_tokens),

"labels": torch.tensor(labels),

}

We can examine what one of these training examples looks like:

dataset = ArithmeticDataset(max_digits=5)

instance = dataset[0]

list(zip(dataset.tokenizer.decode(instance["input_ids"].tolist()), instance["labels"].tolist()))

[('0', -100),

('2', -100),

('2', -100),

('+', -100),

('8', -100),

('2', -100),

('3', -100),

('3', -100),

('=', -100),

('8', 8),

('4', 4),

('5', 5),

('3', 3),

('$', 14),

('$', -100),

('$', -100),

('$', -100),

('$', -100)]

Train!

device = torch.device("cuda") # must use cuda because of flash-attn

assert torch.cuda.is_available()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

model = ArithmeticTransformer(recurrent_block_size=1, num_recurrences=16).to(device)

At this point, the model has been initialized with random weights, so it should do no better than randomly generating strings on the tokenizer alphabet, which is indeed what we see:

from statistics import mean

from math import exp

def generate_answer(model, num1: int, num2: int, max_digits=150):

"""

Compute the answer outputted by the model along with the perplexity of the correct answer.

"""

tokenizer = model.tokenizer

problem = str(num1)[::-1] + "+" + str(num2)[::-1] + "="

problem_tokens: list[int] = tokenizer.encode(problem, add_eos=False)

input_tokens = list(problem_tokens)

answer = str(num1 + num2)[::-1] + "$"

answer_tokens = tokenizer.encode(answer, add_eos=False)

full_statement_tokens = torch.tensor(input_tokens + answer_tokens).unsqueeze(0).to(device)

generated_tokens = []

correct_logprobs = []

model.eval() # as opposed to model.train()

tokens_so_far = len(input_tokens)

with torch.no_grad(): # disables gradient tracking

for _ in range(max_digits):

outputs = model(torch.tensor(input_tokens).unsqueeze(0).to(device))

next_token_logits = outputs["logits"][0, -1, :]

predicted_token = next_token_logits.argmax().item()

if predicted_token == tokenizer.eos_id:

break

else:

generated_tokens.append(predicted_token)

input_tokens.append(predicted_token)

for i, correct_token in enumerate(answer_tokens, 0):

outputs = model(full_statement_tokens[:,:len(problem_tokens)+i])

next_token_logits = outputs["logits"][0, -1, :]

logprobs = nn.LogSoftmax(dim=0)(next_token_logits)

correct_logprobs.append(logprobs[correct_token].item())

perplexity_of_correct_answer = exp(-mean(correct_logprobs))

return (tokenizer.decode(generated_tokens, remove_eos=False)[::-1], perplexity_of_correct_answer)

def check_answer(model, num1, num2, max_digits=150):

gen_answer, correct_answer_perplexity = generate_answer(model, num1, num2)

correctness = "correct" if str(num1+num2) == gen_answer else "incorrect"

print(f"Output {correctness}:\n\t{num1}+{num2}={gen_answer}\n\t{correct_answer_perplexity=}")

print(check_answer(model, 1, 1))

Output incorrect:

1+1=================

correct_answer_perplexity=7775.605965354573

None

Now we want to do some training on random instances, matching the 20M examples from the paper.

import time

import random

import torch

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def train_arithmetic_model(

model,

max_digits=20,

num_samples=20_000_000,

batch_size=95,

num_workers=4,

learning_rate=1e-4,

max_batches=None,

save_interval=5000,

device="cuda",

save_path="./model_{}.pt"

):

t0 = time.time()

dataset = ArithmeticDataset(

max_digits=max_digits,

num_samples=num_samples,

)

dataloader = DataLoader(

dataset,

batch_size=batch_size,

num_workers=num_workers,

pin_memory=True,

)

optimizer = torch.optim.AdamW(model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

scaler = torch.amp.GradScaler(device)

losses = []

train_tokens = 0

model.train()

for batch_num, batch in enumerate(dataloader):

batch = {k: v.to(device) for k, v in batch.items()}

with torch.amp.autocast(device):

output_full = model(**batch)

loss_full = output_full["loss"]

random_recur = random.randint(1, model.decoder_stack.num_recurrences)

if random_recur != model.decoder_stack.num_recurrences:

output_partial = model(**batch, num_recurrences=random_recur)

loss_partial = output_partial["loss"]

loss = 0.5 * (loss_full + loss_partial)

else:

loss = loss_full

optimizer.zero_grad()

scaler.scale(loss).backward()

scaler.step(optimizer)

scaler.update()

losses.append(loss.item())

train_tokens += torch.sum(batch["labels"] != -100).item()

if (batch_num % save_interval == 0):

# Save model checkpoint

save_file = save_path.format(batch_num)

torch.save(model.state_dict(), save_file)

print(f"\nSaved model to {save_file}")

# Print progress and check answers

print(f"Batch {batch_num}, loss={losses[-1]} t={time.time()-t0:0.1f}s")

check_answer(model, 1, 1)

check_answer(model, 57, 24)

check_answer(model, 999999, 8888)

check_answer(model, int('789' * 50), int('12' * 20))

elif batch_num % 50 == 0:

print(".", end="")

if max_batches is not None and batch_num >= max_batches:

# Save final model

save_file = save_path.format(batch_num)

torch.save(model.state_dict(), save_file)

print(f"\nSaved final model to {save_file}")

break

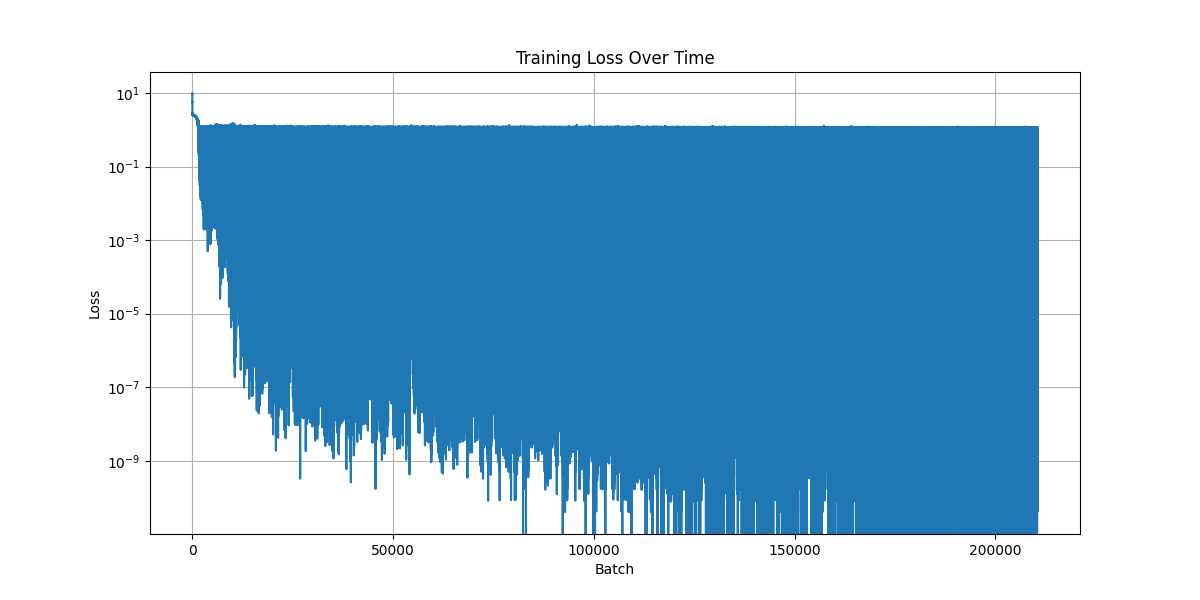

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.plot(losses)

plt.title('Training Loss Over Time')

plt.xlabel('Batch')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.yscale('log')

plt.grid(True)

# Save the plot

plt.savefig('training_losses.png')

plt.close()

# Clean up gradients and memory

model.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)

del optimizer

del scaler

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

return losses

losses = train_arithmetic_model(

model,

max_digits=20,

num_samples=20_000_000,

batch_size=95,

save_interval=5000

)

from IPython.display import Image, display

display(Image('training_losses.png'))

Saved model to ./model_0.pt

Batch 0, loss=9.62136459350586 t=0.8s

Output incorrect:

1+1==================

correct_answer_perplexity=14581.836010020208

Output incorrect:

57+24===================

correct_answer_perplexity=74972.80264434294

Output incorrect:

999999+8888==================

correct_answer_perplexity=199.9132414846273

Output incorrect:

789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789+1212121212121212121212121212121212121212===========================

correct_answer_perplexity=1637.2590761673289

...................................................................................................

Saved model to ./model_5000.pt

Batch 5000, loss=0.023050425574183464 t=2334.2s

Output incorrect:

1+1=12

correct_answer_perplexity=5985.781926094305

Output correct:

57+24=81

correct_answer_perplexity=1.1549736380920936

Output incorrect:

999999+8888=0008887

correct_answer_perplexity=1.7199512942175632

Output incorrect:

789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789+1212121212121212121212121212121212121212=90101911001911001911001911001911001911001

correct_answer_perplexity=41668.006538249516

...................................................................................................

[...]

Saved model to ./model_200000.pt

Batch 200000, loss=9.66292574844374e-08 t=93345.3s

Output correct:

1+1=2

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output correct:

57+24=81

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output correct:

999999+8888=1008887

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output incorrect:

789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789+1212121212121212121212121212121212121212=89891001911001911001911001911001911001911001

correct_answer_perplexity=18841.785424248348

...................................................................................................

Saved model to ./model_205000.pt

Batch 205000, loss=6.846190281351028e-10 t=95679.4s

Output correct:

1+1=2

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output correct:

57+24=81

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output correct:

999999+8888=1008887

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0000480034748582

Output incorrect:

789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789+1212121212121212121212121212121212121212=787791012111001911001911001911001911001911001

correct_answer_perplexity=72940.13920164928

...................................................................................................

Saved model to ./model_210000.pt

Batch 210000, loss=5.450771212167638e-08 t=98017.4s

Output correct:

1+1=2

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output correct:

57+24=81

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0

Output correct:

999999+8888=1008887

correct_answer_perplexity=1.0000000298023193

Output incorrect:

789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789789+1212121212121212121212121212121212121212=789809789789791001911001910901911001911001911001911001

correct_answer_perplexity=140499.23622358224

..........

That loss graph doesn’t look very good. Some batches had very, very low loss, but even after a lot of examples, some batches had high loss, within a few orders of magnitude of where we started. I suspect this is caused by two things:

- The batch size is small, so there is higher variance in loss across batches.

- Since loss is an average of the layer looped 16 times and a random number of times <16, the random number will sometimes be small, which seems to produce much worse outcomes in testing below.

More notes on terminology:

Perplexity, or “that’s so random”

This is an average measure of how unlikely a piece of text is, defined as the reciprocal of the geometric mean of token probabilities (conditioned on previous token probabilities) in that piece of text:

\[\left(\prod_{i=1}^n p\left(t_i|t_1\ldots t_{i-1}\right) \right)^{-1/n}\]Text with 100% probability of each token has a perplexity of 1. Any sequence of H (heads) and T (tails) fair coin flips would have a perplexity of $2=\frac{1}{1/2}$. Low probability text has much higher perplexity.

It’s often computed from log probabilities for numerical stability, or because that’s what e.g. OpenAI’s API endpoints return. There the formula is:

\[\exp\left( - \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \log\left(p\left(t_i|t_1\ldots t_{i-1}\right)\right)\right)\]torch.amp.autocast

“AMP” stands for “Automatic Mixed Precision”. This prevents cuda mixed precision errors if we try to add a float16 to a float32.

OOD numbers

Now we can examine out-of-distribution numbers (more than 20 digits) to see how well it does. To limit the computation time, we’ll only look at pairs of numbers of the same length.

import random

import torch

def run_batch(model, digits1, digits2, n_batch, num_recurrences=None, seed=None) -> torch.tensor:

model.eval()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

if seed is not None:

randint = random.Random(seed).randint

else:

randint = random.randint

with torch.no_grad():

instances = [

(

randint(0 if digits1 == 1 else 10**(digits1-1), 10**digits1-1),

randint(0 if digits2 == 1 else 10**(digits2-1), 10**digits2-1),

)

for _ in range(n_batch)

]

strings = [

f"{str(k1)[::-1]}+{str(k2)[::-1]}=" for k1, k2 in instances

]

batch = torch.tensor([

model.tokenizer.encode(instance, add_eos=False) for instance in strings

]).to(device)

for iteration in range(max(digits1, digits2) + 2): # +2 for potential carry

logits = model(batch, num_recurrences=num_recurrences)["logits"]

last_token_logits = logits[:, -1, :]

next_tokens = torch.argmax(last_token_logits, dim=-1).unsqueeze(-1)

batch = torch.cat([batch, next_tokens], dim=-1)

results = [

model.tokenizer.decode(sequence, remove_eos=False)

for sequence in batch.tolist()

]

return results

%time lgs = run_batch(model, 3, 5, 500)

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

CPU times: user 1.69 s, sys: 80.2 ms, total: 1.77 s

Wall time: 1.77 s

from typing import NamedTuple

class EvalResult(NamedTuple):

total: int

correct: int

import re

def eval_batch_results(results: list[str]) -> EvalResult:

correct = 0

for result in results:

match = re.match(r"(\d+)[+](\d+)=(\d+)[$]", result)

if match:

n1, n2, answer = [int(x[::-1]) for x in match.groups()]

if n1 + n2 == answer:

correct += 1

return EvalResult(total=len(results), correct=correct)

eval_batch_results(run_batch(model, 20, 20, 100, seed=1))

EvalResult(total=100, correct=100)

def evaluate_digit_combinations(model, n_digits, seed=None, num_recurrences=16, n_batch=100):

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from IPython.display import clear_output

import time

# Initialize results matrix with NaN

results = np.full((n_digits, n_digits), np.nan)

def plot_current_results(results, current_size):

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 12))

# Create a masked array to show only computed values (non-NaN)

masked_results = np.ma.masked_array(results, mask=np.isnan(results))

hm = sns.heatmap(masked_results,

xticklabels=range(1, n_digits+1),

yticklabels=range(1, n_digits+1),

cmap='viridis',

vmin=0,

vmax=1)

plt.gca().invert_yaxis()

plt.xlabel('Number of digits (second number)')

plt.ylabel('Number of digits (first number)')

plt.title(f'Addition Accuracy by Number of Digits (Computing {current_size}x{current_size} square)')

plt.colorbar(hm.collections[0], label='Accuracy')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Run evaluation in expanding squares

start_time = time.time()

total_computed = 0

for size in range(1, n_digits + 1):

for i in range(size): # Row index

for j in range(size): # Column index

if not np.isnan(results[i, j]):

continue

batch_results = run_batch(model,

digits1=i+1,

digits2=j+1,

n_batch=n_batch,

num_recurrences=num_recurrences,

seed=seed)

eval_result = eval_batch_results(batch_results)

accuracy = eval_result.correct / eval_result.total

results[i, j] = accuracy

total_computed += 1

print(f"digits1={i+1}, digits2={j+1}: accuracy={accuracy:.2f}")

elapsed_time = time.time() - start_time

progress = total_computed / (n_digits * n_digits)

if progress > 0:

estimated_total = elapsed_time / progress

remaining = estimated_total - elapsed_time

print(f"Estimated time remaining: {remaining/60:.1f} minutes")

# After each square is complete, clear output and show current progress

clear_output(wait=True)

plot_current_results(results, size)

print(f"Completed {size}x{size} square")

print(f"Current average accuracy: {np.nanmean(results):.3f}")

print(f"Best performance so far: {np.nanmax(results):.3f}")

print(f"Worst performance so far: {np.nanmin(results):.3f}")

return results

Looping over different numbers of recurrences

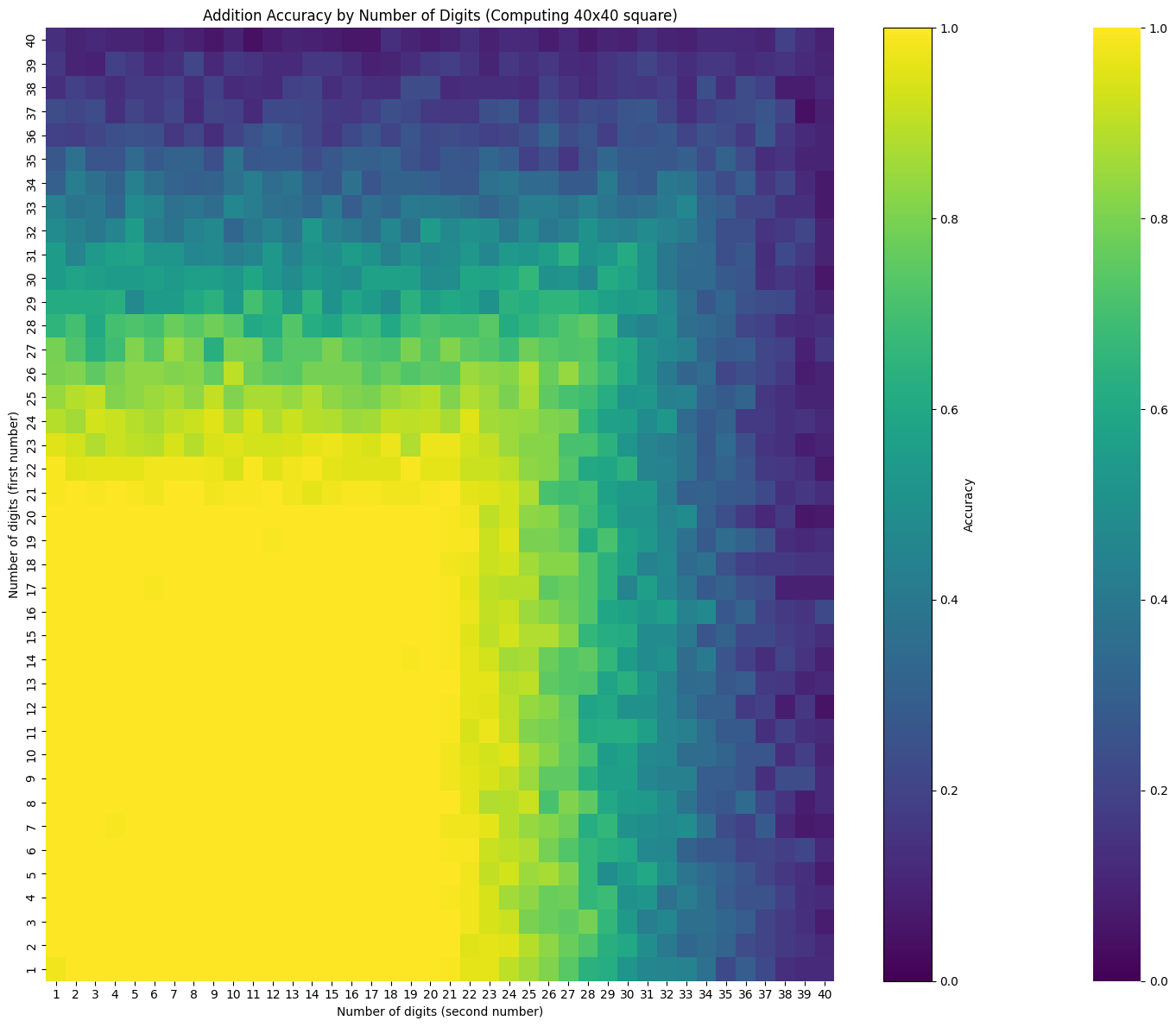

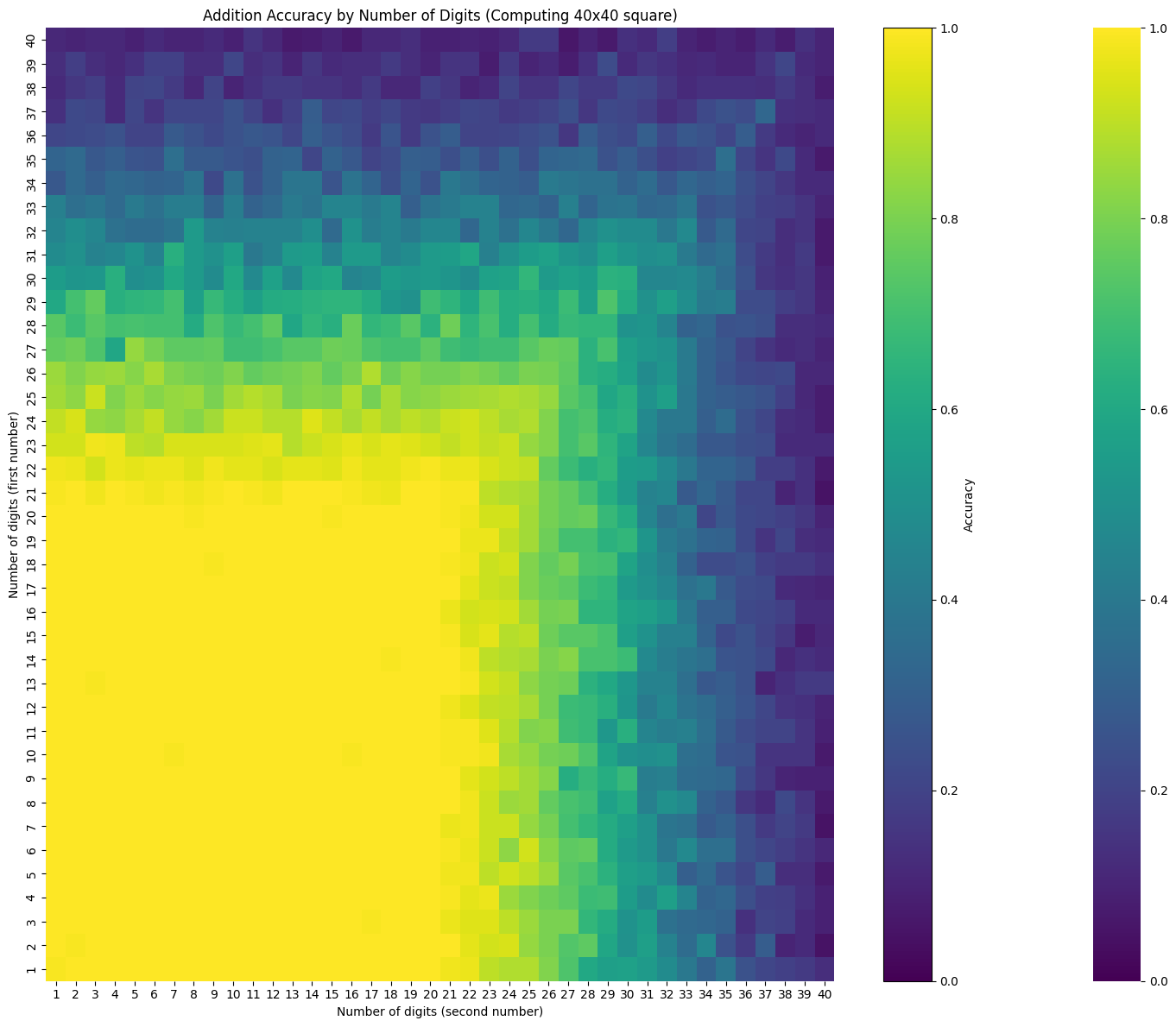

16 loops

evaluate_digit_combinations(model, n_digits=40, seed=42, num_recurrences=16, n_batch=100)

Current average accuracy: 0.613

Best performance so far: 1.000

Worst performance so far: 0.040

1 loop

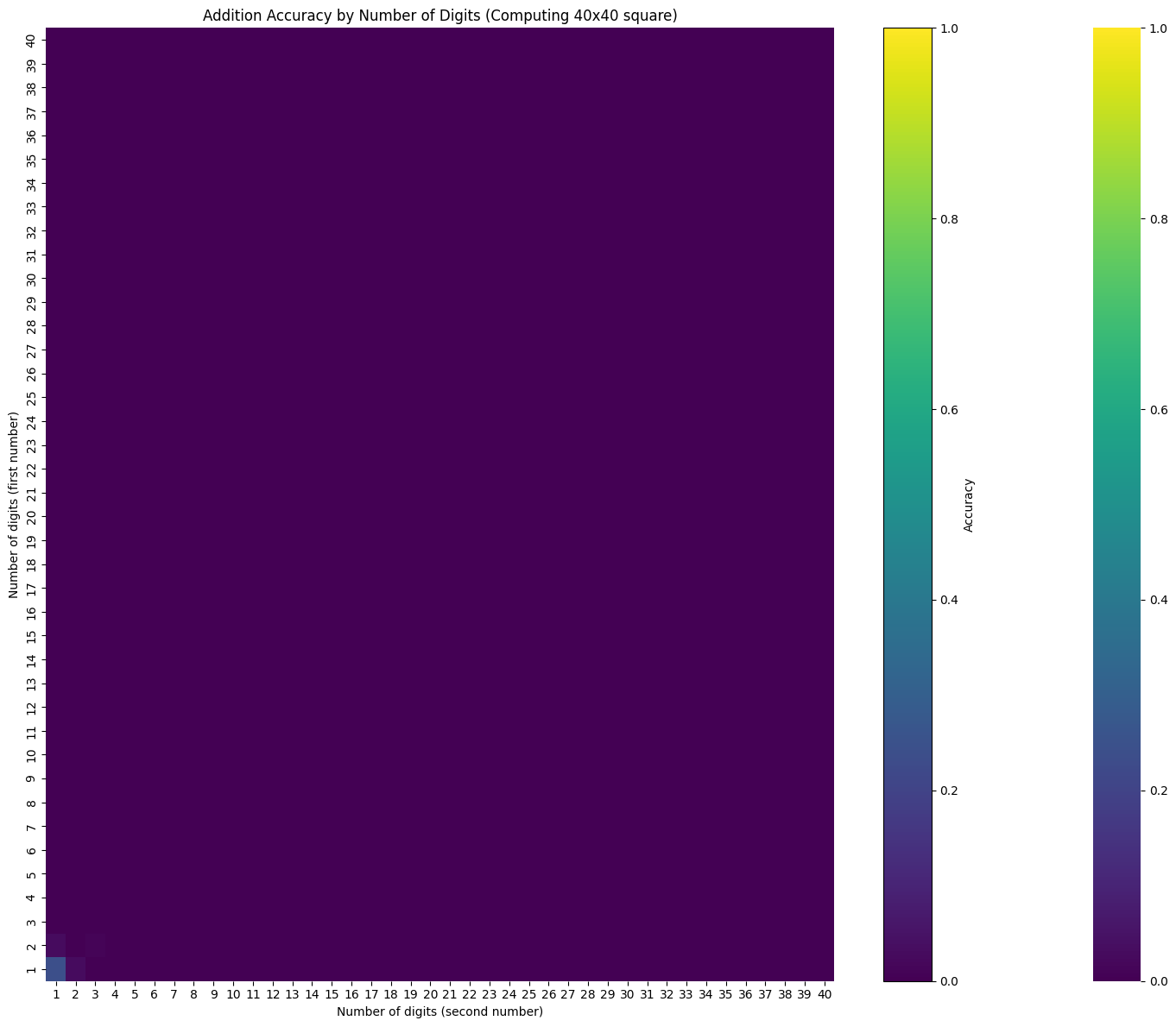

evaluate_digit_combinations(model, n_digits=40, seed=42, num_recurrences=1, n_batch=100)

Current average accuracy: 0.000

Best performance so far: 0.240

Worst performance so far: 0.000

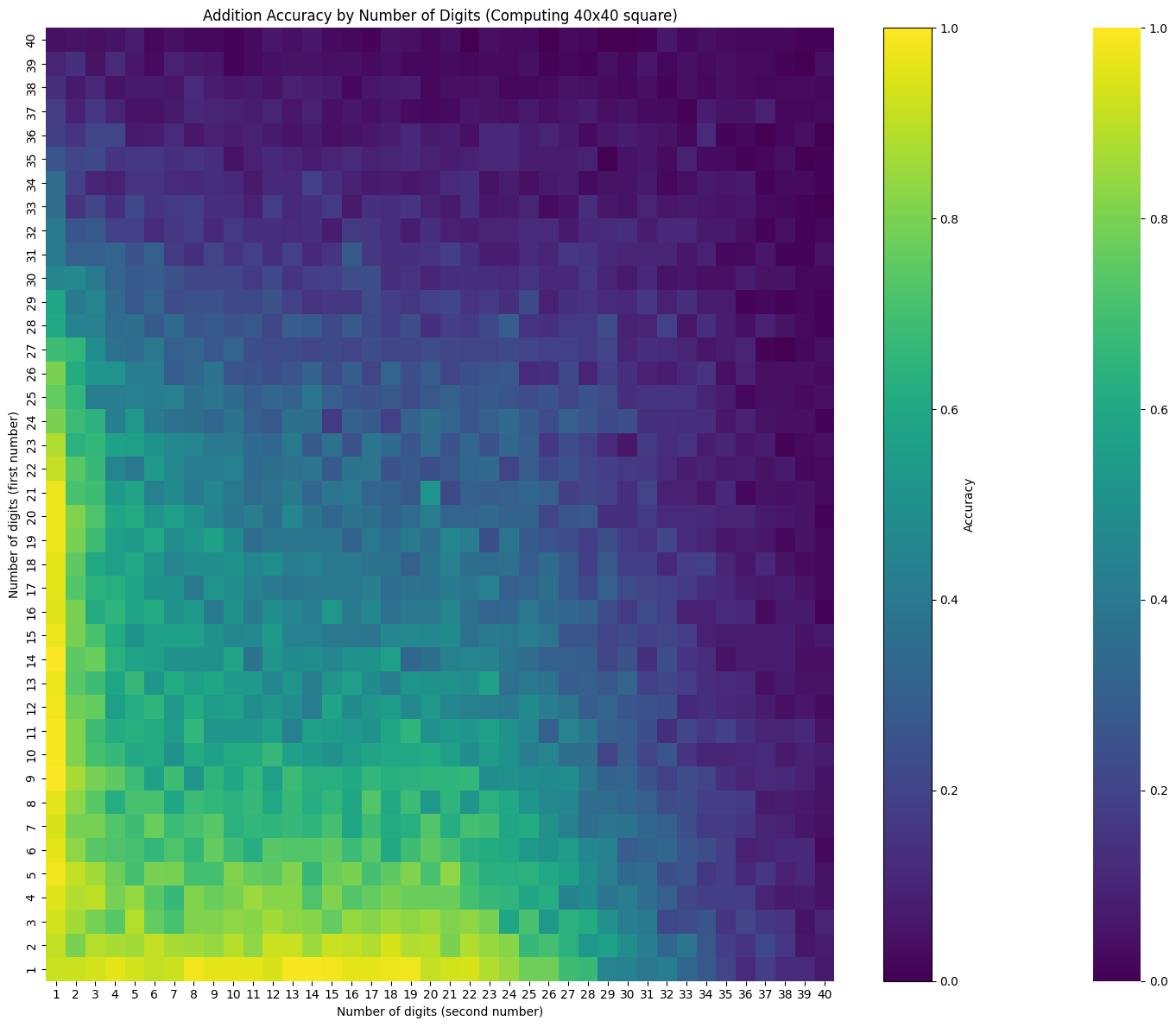

2 loops

evaluate_digit_combinations(model, n_digits=40, seed=42, num_recurrences=2, n_batch=100)

Current average accuracy: 0.320

Best performance so far: 1.000

Worst performance so far: 0.000

8 loops

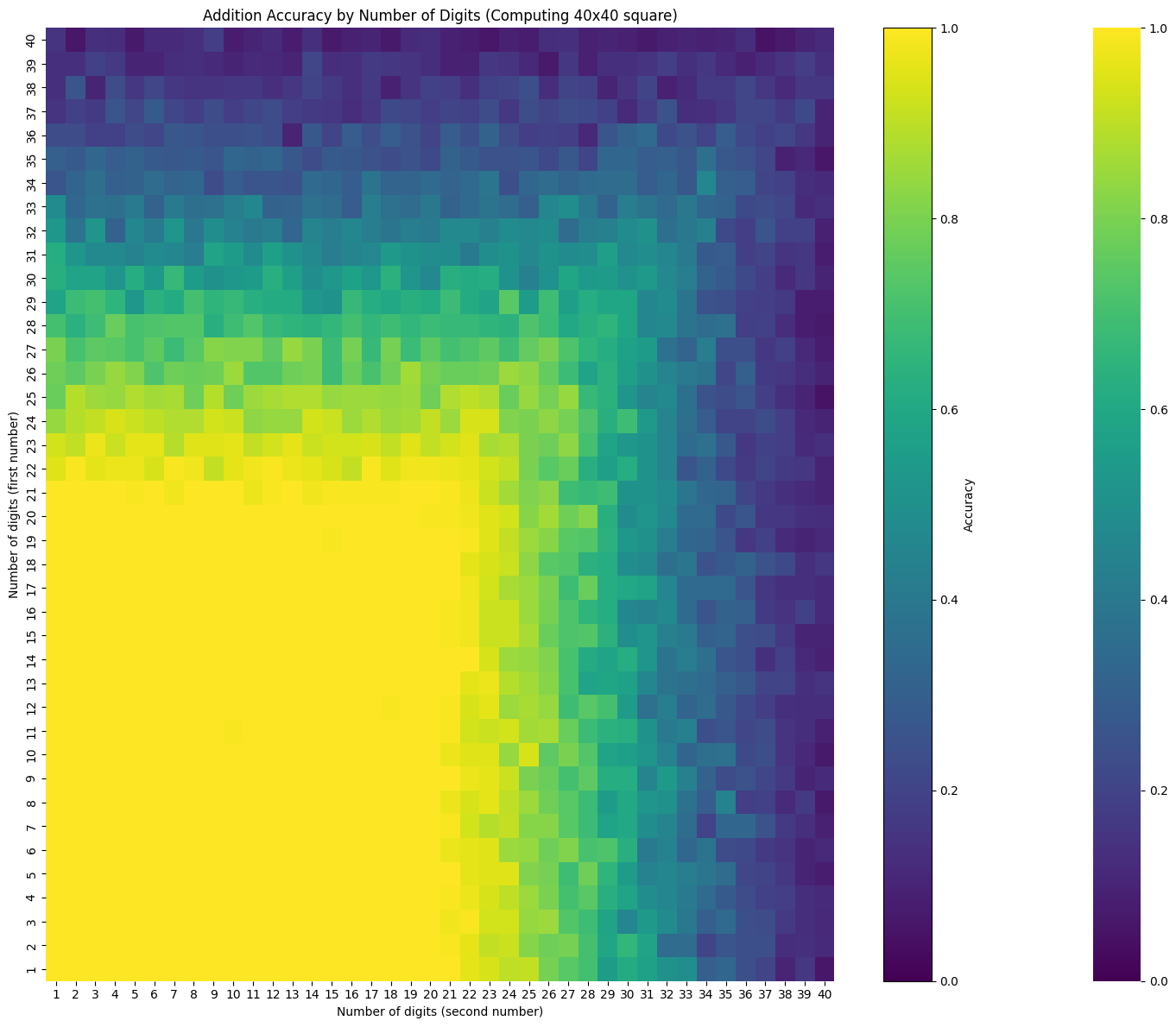

evaluate_digit_combinations(model, n_digits=40, seed=42, num_recurrences=8, n_batch=100)

Current average accuracy: 0.611

Best performance so far: 1.000

Worst performance so far: 0.050

32 loops

evaluate_digit_combinations(model, n_digits=40, seed=42, num_recurrences=32, n_batch=100)

Current average accuracy: 0.613

Best performance so far: 1.000

Worst performance so far: 0.050

Overall notes

My attempt to reproduce the results of the paper was only partly successful. We saw it learn arithmetic on the train distribution, saw some OOD generalization (though not all that much), and observed variable accuracy at different loop numbers.

However, the overall accuracy was worse than in the paper. I think this comes down to two things:

- I tried creating abacus positional encoding vectors for the entire context length. This meant each encoding vector got fewer gradients adjusting it than it did in the paper.

- I only ran the single-layer looped 16 times case, which was the worst performer in the paper. It was also much faster on my GPU. I did few training runs on 8x2, but didn’t rigorously record them because various other things were broken at that point. I think for future projects, I’ll try to get the code basically working on small models locally and send to cloud GPUs for larger training runs. The RTX 4060 can do something like 15 TFLOP/s, while an H100 can do up to 1979 TFLOP/s, so even at >$5/hour, it should be able to complete these sorts of experiments much more quickly.