This post contains my notes from trying to understand where the Poisson distribution comes from.

Interlude on limit definition of exp \exp exp

To start out, let’s understand the definition that is commonly given for e e e e : = lim x → ∞ ( 1 + 1 x ) x e:= \lim_{x\to\infty} \left(1 + {1 \over x}\right)^x e := lim x → ∞ ( 1 + x 1 ) x

It’s probably better to think of this in terms of e x e^x e x exp ( y ) : = lim x → ∞ ( 1 + y x ) x \exp(y) := \lim_{x\to\infty} \left(1 + {y \over x}\right)^x exp ( y ) := lim x → ∞ ( 1 + x y ) x

The existence of this limit can be shown by Bernoulli’s inequality . Now note:

exp ( 0 ) = 1 \exp(0)=1 exp ( 0 ) = 1 exp ( a ⋅ b ) = ( exp ( a ) ) b \exp(a\cdot b)=(\exp(a))^b exp ( a ⋅ b ) = ( exp ( a ) ) b exp ( a + b ) = exp ( a ) ⋅ exp ( b ) \exp(a + b) = \exp(a) \cdot \exp(b) exp ( a + b ) = exp ( a ) ⋅ exp ( b ) d d x exp ( x ) = exp ( x ) {d \over dx} \exp(x) = \exp(x) d x d exp ( x ) = exp ( x )

(1) follows immediately from the definition.

To show (2), we have:

exp ( a b ) = lim x → ∞ ( 1 + a b x ) x = lim q → ∞ ( 1 + a q ) b ⋅ q ( substitute q = x / b ) = ( lim q → ∞ ( 1 + a q ) q ) b = ( exp ( a ) ) b \begin{aligned}

\exp(ab) & = \lim_{x\to\infty} \left(1 + {ab \over x}\right)^x \\

& = \lim_{q\to\infty} \left(1 + {a \over q}\right)^{b\cdot q} \quad \left(\textrm{substitute } q=x/b\right) \\

& = \left(\lim_{q\to\infty} \left(1 + {a \over q}\right)^q\right)^b \\

& = \left(\exp(a)\right)^b \\

\end{aligned} exp ( ab ) = x → ∞ lim ( 1 + x ab ) x = q → ∞ lim ( 1 + q a ) b ⋅ q ( substitute q = x / b ) = ( q → ∞ lim ( 1 + q a ) q ) b = ( exp ( a ) ) b For (3):

exp ( a + b ) = lim x → ∞ ( 1 + a + b x ) x = lim q → ∞ ( 1 + 1 q ) q ⋅ ( a + b ) ( substitute q = x a + b ) = ( lim q → ∞ ( 1 + 1 q ) q ) a + b = ( exp ( 1 ) ) a + b = exp ( 1 ) a ⋅ exp ( 1 ) b = exp ( a ) ⋅ exp ( b ) \begin{aligned}

\exp(a+b) & = \lim_{x\to\infty} \left(1 + {a+b \over x}\right)^x \\

& = \lim_{q\to\infty} \left(1 + {1 \over q}\right)^{q\cdot (a+b)} \quad \left(\textrm{substitute } q={x\over a+b}\right) \\

& = \left(\lim_{q\to\infty} \left(1 + {1 \over q}\right)^q\right)^{a+b} \\

& = \left(\exp(1)\right)^{a+b} \\

& = \exp(1)^a\cdot \exp(1)^b \\

& = \exp(a)\cdot \exp(b) \\

\end{aligned} exp ( a + b ) = x → ∞ lim ( 1 + x a + b ) x = q → ∞ lim ( 1 + q 1 ) q ⋅ ( a + b ) ( substitute q = a + b x ) = ( q → ∞ lim ( 1 + q 1 ) q ) a + b = ( exp ( 1 ) ) a + b = exp ( 1 ) a ⋅ exp ( 1 ) b = exp ( a ) ⋅ exp ( b ) For (4), we have:

d d x exp ( x ) = lim δ → 0 exp ( x + δ ) − exp ( x ) δ = lim δ → 0 exp ( x ) exp ( δ ) − exp ( x ) δ = exp ( x ) ( lim δ → 0 exp ( δ ) − 1 δ ) = exp ( x ) ( lim δ → 0 ( lim y → ∞ ( 1 + 1 / y ) y ) δ − 1 δ ) = exp ( x ) ( lim δ → 0 ( ( 1 + δ ) 1 δ ) δ − 1 δ ) ( letting y = 1 / δ ) = exp ( x ) ( lim δ → 0 ( 1 + δ ) − 1 δ ) = exp ( x ) ( lim δ → 0 δ δ ) = exp ( x ) \begin{aligned}

{d \over dx} \exp(x) &= \lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{\exp(x+\delta) - \exp(x)}{\delta} \\

&= \lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{\exp(x)\exp(\delta) - \exp(x)}{\delta} \\

&= \exp(x)\left(\lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{\exp(\delta) - 1}{\delta} \right) \\

&= \exp(x)\left(\lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{\left(\lim_{y\to\infty}(1 + 1/y)^y\right)^\delta - 1}{\delta} \right) \\

&= \exp(x)\left(\lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{\left((1 + \delta)^{1\over \delta}\right)^\delta - 1}{\delta} \right) \quad \left(\textrm{letting }y=1/\delta\right)\\

&= \exp(x)\left(\lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{(1 + \delta) - 1}{\delta} \right) \\

&= \exp(x)\left(\lim_{\delta\to 0} \frac{\delta}{\delta} \right)\\

&= \exp(x) \\

\end{aligned} d x d exp ( x ) = δ → 0 lim δ exp ( x + δ ) − exp ( x ) = δ → 0 lim δ exp ( x ) exp ( δ ) − exp ( x ) = exp ( x ) ( δ → 0 lim δ exp ( δ ) − 1 ) = exp ( x ) ( δ → 0 lim δ ( lim y → ∞ ( 1 + 1/ y ) y ) δ − 1 ) = exp ( x ) δ → 0 lim δ ( ( 1 + δ ) δ 1 ) δ − 1 ( letting y = 1/ δ ) = exp ( x ) ( δ → 0 lim δ ( 1 + δ ) − 1 ) = exp ( x ) ( δ → 0 lim δ δ ) = exp ( x ) Poisson (as a limit of Binomial)

Note: follows this post .

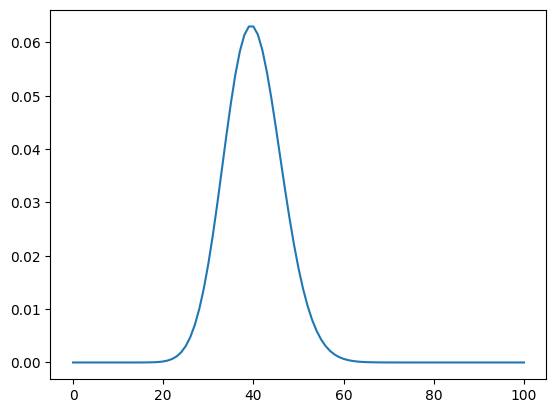

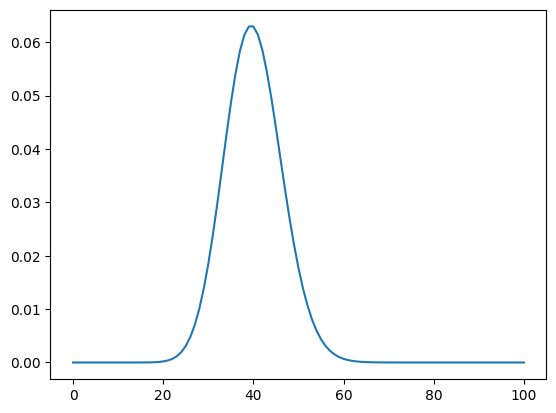

As a motivating example, consider the number of customers to a grocery store in a town, where every person in the town has probability p p p

The PMF for this looks like:

Now suppose we have n n n n n n p p p λ \lambda λ n n n p p p λ = n p \lambda = np λ = n p p = λ n p = {\lambda \over n} p = n λ

Then since this is a binomial trial, we have:

P ( X = k ) = ( n k ) ( λ n ) k ( 1 − λ n ) n − k = n ! k ! ( n − k ) ! ( λ n ) k ( 1 − λ n ) n − k P(X=k) = {n \choose k} \left({\lambda \over n}\right)^k \left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^{n-k} = {n! \over k!(n-k)!} \left({\lambda \over n}\right)^k \left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^{n-k} P ( X = k ) = ( k n ) ( n λ ) k ( 1 − n λ ) n − k = k ! ( n − k )! n ! ( n λ ) k ( 1 − n λ ) n − k

Taking the limit as n → ∞ n\to\infty n → ∞

P ∞ ( X = k ) = λ k k ! ⋅ lim n → ∞ n ! ( n − k ) ! ( 1 n ) k ( 1 − λ n ) n − k = λ k k ! ⋅ lim n → ∞ n ! n k ( n − k ) ! ( 1 − λ n ) n ( 1 − λ n ) − k Canceling like terms, we end up with k terms of size O ( n ) on top and bottom, so the first term is 1. Thus: = λ k k ! ⋅ lim n → ∞ ( 1 − λ n ) n ( 1 − λ n ) − k Since k is fixed. The second term is 1: = λ k k ! ⋅ lim n → ∞ ( 1 − λ n ) n = λ k e − λ k ! \begin{aligned}

P_\infty(X=k) &= {\lambda^k \over k!} \cdot \lim_{n\to\infty} {n! \over (n-k)!} \left({1 \over n}\right)^k \left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^{n-k} \\

&= {\lambda^k \over k!} \cdot \lim_{n\to\infty} {n! \over n^k(n-k)!} \left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^n\left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^{-k} \\

& \textrm{Canceling like terms, we end up with }k\textrm{ terms of size }O(n)\textrm{ on top and bottom, so the first term is 1. Thus:} \\

&= {\lambda^k \over k!} \cdot \lim_{n\to\infty} \left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^n\left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^{-k} \\

& \textrm{Since }k\textrm{ is fixed. The second term is 1:} \\

&= {\lambda^k \over k!} \cdot \lim_{n\to\infty} \left(1 - {\lambda \over n}\right)^n \\

&= {\lambda^k e^{-\lambda} \over k!} \\

\end{aligned} P ∞ ( X = k ) = k ! λ k ⋅ n → ∞ lim ( n − k )! n ! ( n 1 ) k ( 1 − n λ ) n − k = k ! λ k ⋅ n → ∞ lim n k ( n − k )! n ! ( 1 − n λ ) n ( 1 − n λ ) − k Canceling like terms, we end up with k terms of size O ( n ) on top and bottom, so the first term is 1. Thus: = k ! λ k ⋅ n → ∞ lim ( 1 − n λ ) n ( 1 − n λ ) − k Since k is fixed. The second term is 1: = k ! λ k ⋅ n → ∞ lim ( 1 − n λ ) n = k ! λ k e − λ That is the standard PMF of the Poisson distribution. In our example above, we have λ = 40 \lambda=40 λ = 40